“There are things that Black people are sharing—they are being more vulnerable with themselves, asking for advocacy, asking for non-Black people, particularly white people to come in and do the work and to keep moving forward,” says Dr. Akilah Cadet, who has made a career out of guiding non-Black people into allyship with the Black community. But at the end of the day, what she really needs is for white people to start guiding themselves and each other.

“The way that white people can continue with allyship is for them to really understand that I am tired. I’m tired of asking for them to be allies. I’m honored to work with beautiful companies and brands all over the world, but they aren’t coming to me to keep them amazing and great. They’re coming to me to make sure they’re protecting their workforce, they’re representing their consumer, and that they’re holding themselves accountable for whom they’re bringing in—their partnerships, their vendors, their brands, their new hires. So, as much as I enjoy doing that work, when that paralysis shows up, like, ’Ooh, we’re not ready for that statement’ or ’Actually, we don’t want to say that we’re anti-racist just yet. We need to figure out what diversity means for us.’ That push and pull that I do on a daily basis is exciting and rewarding and I’m honored to do it, but it’s also exhausting.”

“The way that white people can continue with allyship is for them to really understand that I am tired. I’m tired of asking for them to be allies.”

-Dr. Akilah Cadet

According to Dr. Cadet, the foundation of allyship is never opting out—and realizing that even having the choice to do so is a privilege afforded only to them. “I don’t want to hear, ’Oof, this is too much for me,’ because I don’t have the liberty. I don’t have that choice. If I want any amount of success or any remote cousin of human decency, I have to learn how to live in your space.”

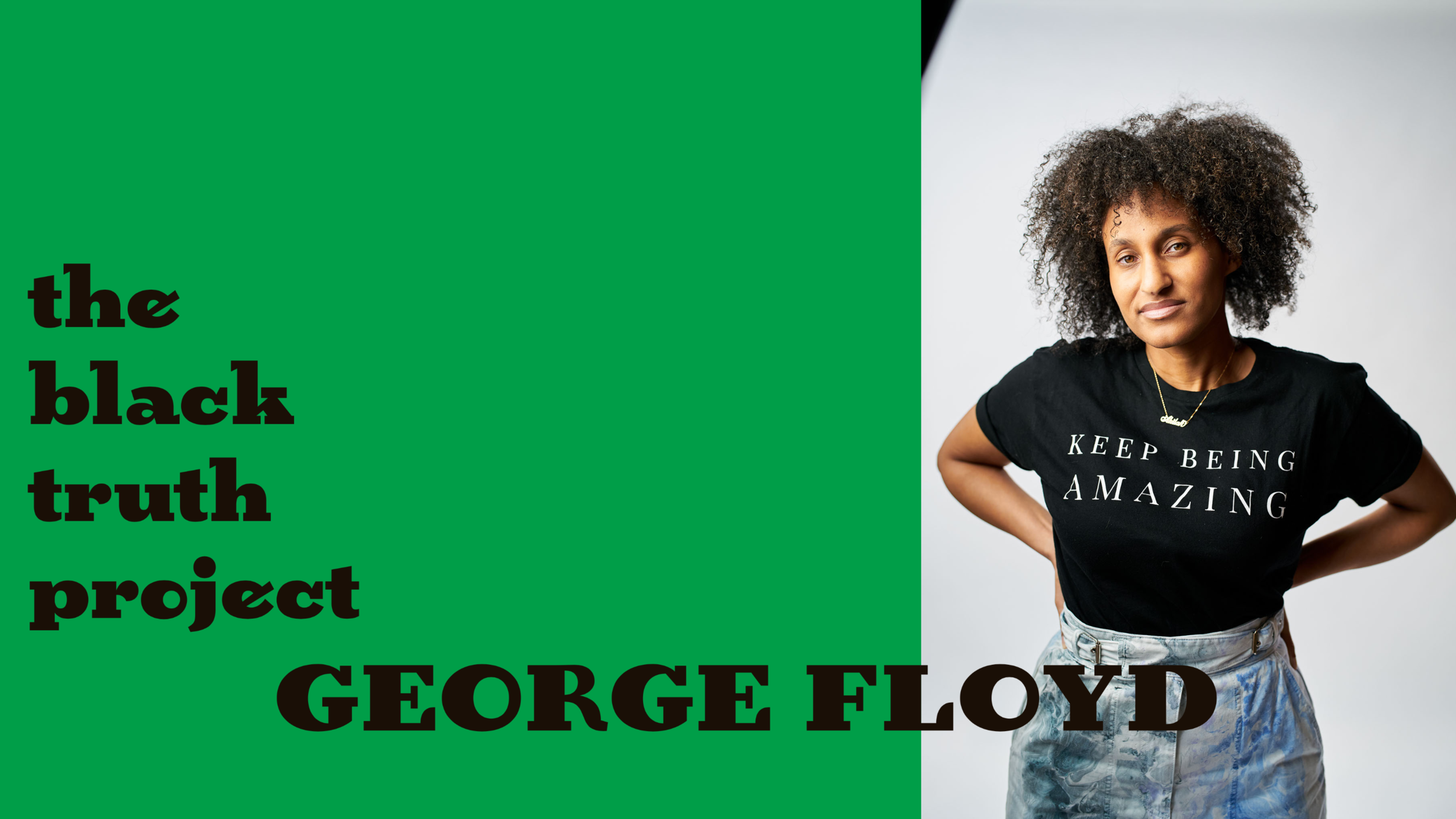

WATCH DR. AKILAH CADET’S FULL BLACK TRUTH VIDEO HERE.

And while America has introduced Peter Limata to some of the most virulent forms of racism and discrimnation, he also recognizes that the country is home to some of the most dedicated activists fighting against it. “One thing that I really appreciate is seeing how many people have been pushing and doing things like this,” he says, referring to The Black Truth Project. “Because of colonialism and racism, we’ve been taught to do things a certain way, and that you cannot stray from that. And so to see an active breaking of those barriers, it’s been something that has changed me. It’s made me realize, yeah, I need to be at that protest, I need to use my voice as well. I think it’s just continued pressure—we can’t let up.”

“I can teach them how to be allies, because sometimes people want to, but they don’t know how to do it.”

-Peter Limata

And as a teacher, he is a vocal advocate for talking about issues of race and discriminaion from an early age. He also hopes that friends, colleagues, and parents from his school will see him as a resource on how to best work for change. “I can teach them how to be allies, because sometimes people want to, but they don’t know how to do it.”

Watch PETER LIMATA’s full Black Truth Video HERE.

KEEP READING.

After the past four years of in-your-face hate and blatant incompetence, it can be easy for those who don’t have battle of discrimination and white supremecy on a daily baisis to feel like the war has been won. But for many, it’s just another opportunity for injustices to go into hiding, and for allies to take their foot off the gas.