Fashion Joins The Fight

When British Vogue was ready to trade fashion for activism, they called in photographer Misan Harriman.

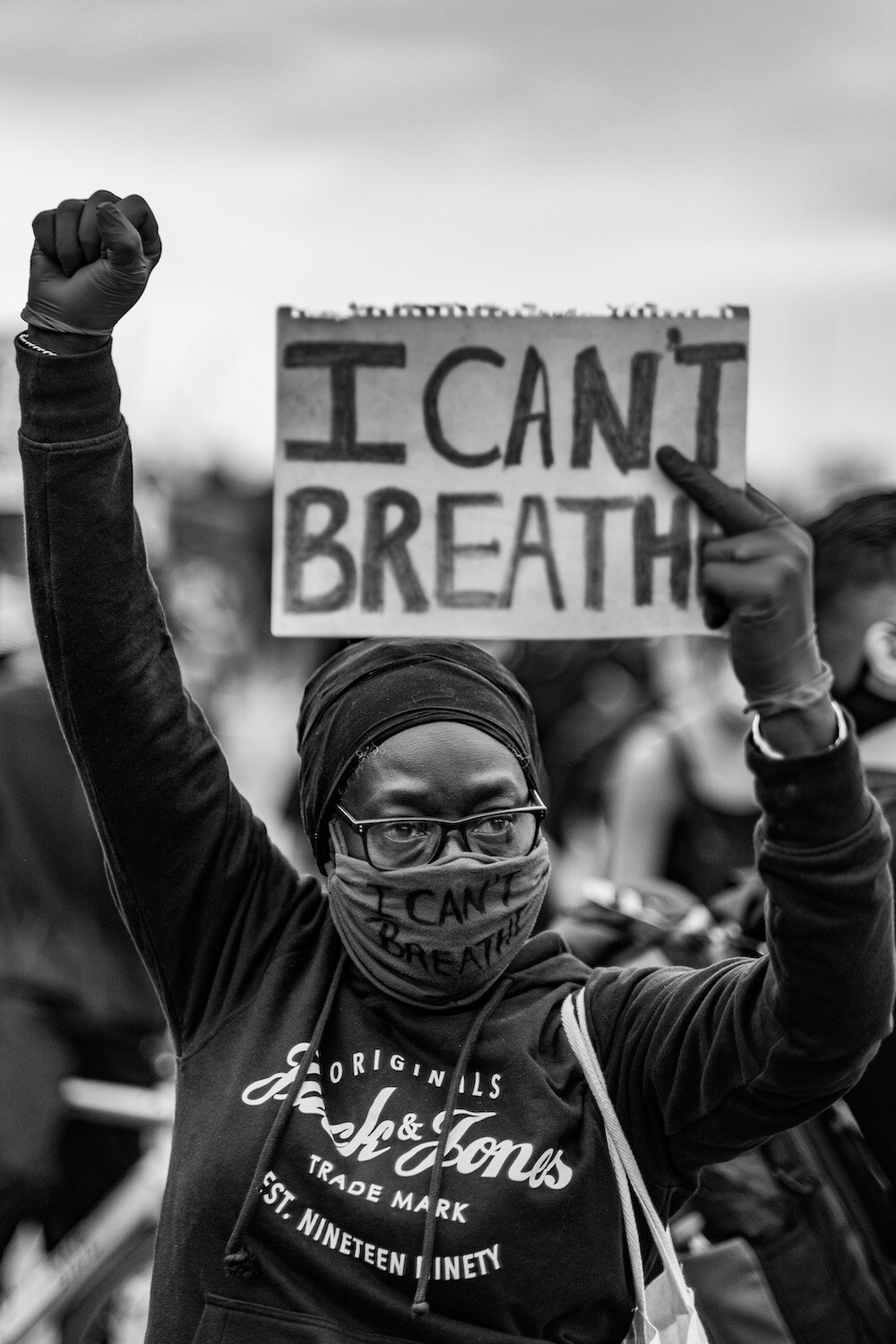

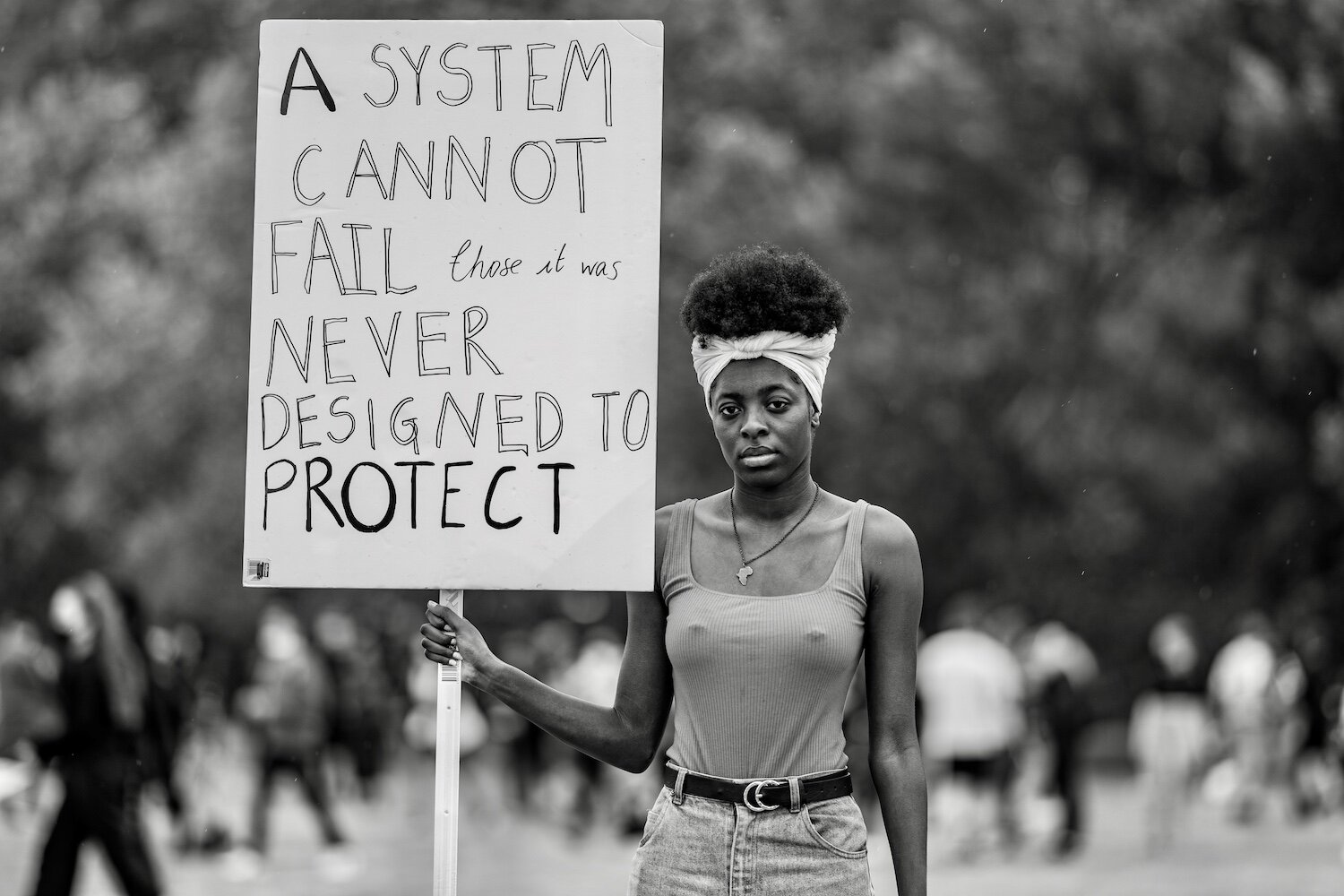

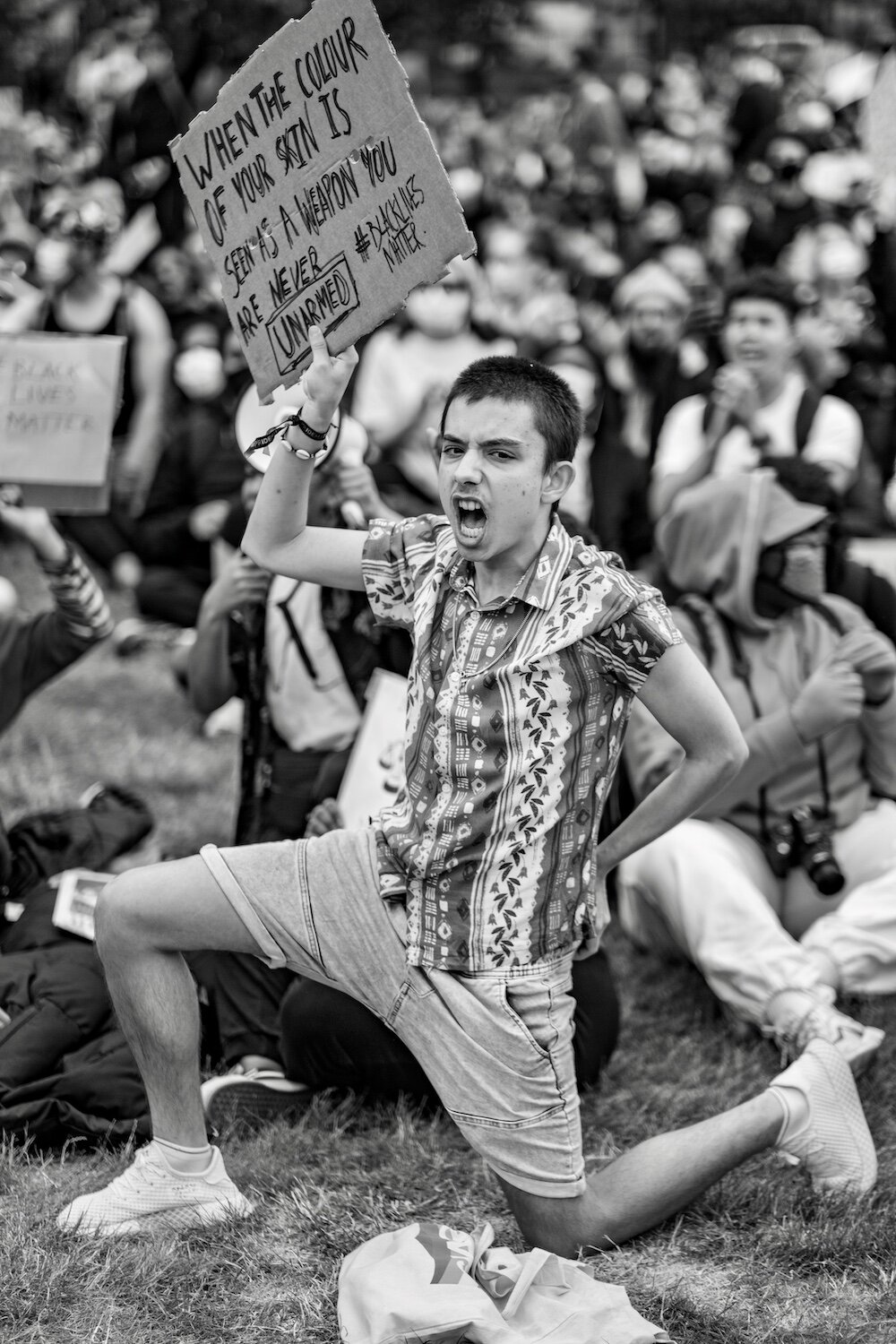

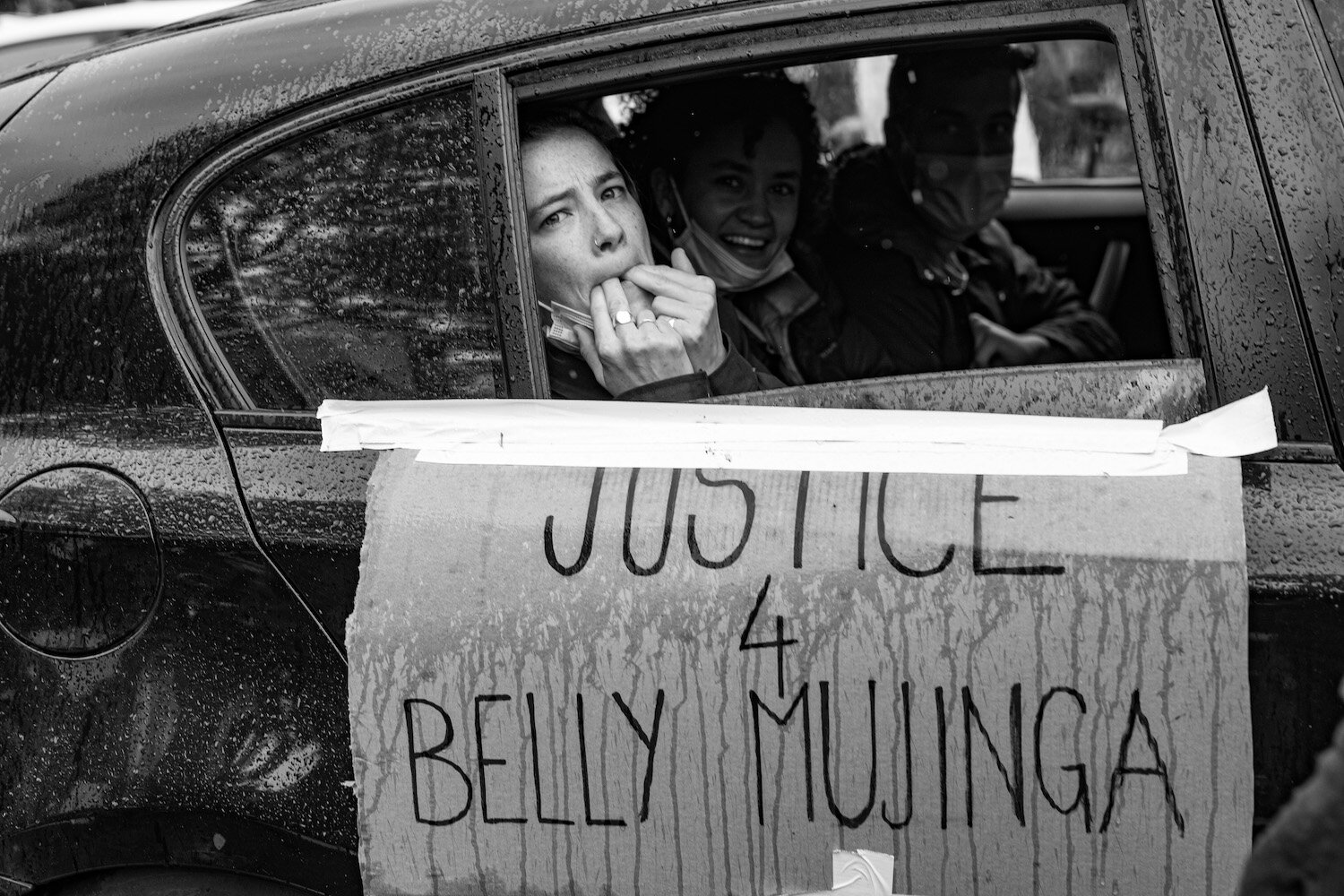

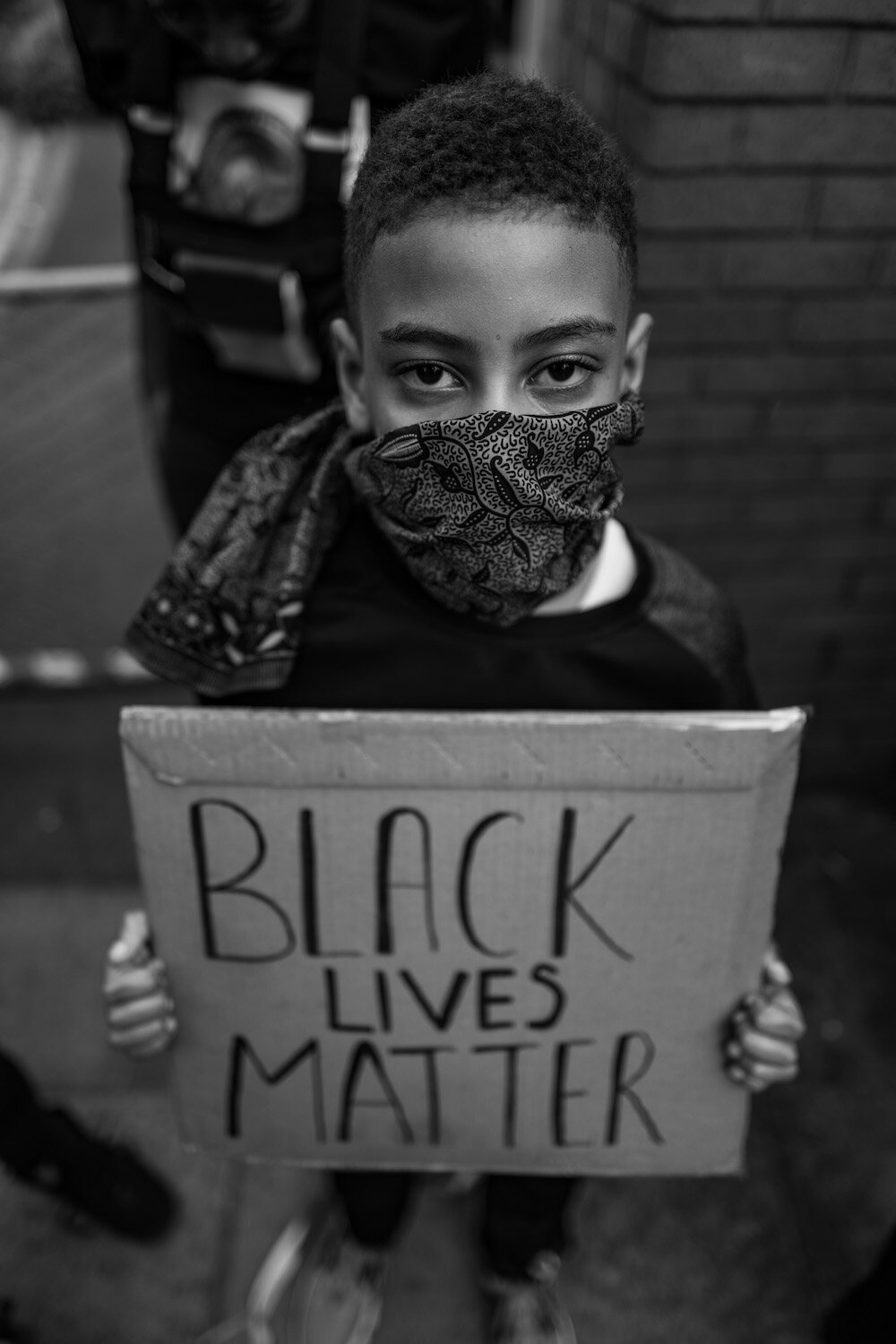

If you’ve been following the worldwide protests sparked by George Floyd’s killing back in May, chances are you’ve seen a photo taken by London-based media curator and photographer Misan Harriman. Always shot in striking monochrome, his powerful images of the Black Lives Matter movement in the UK and beyond have gone viral in recent months, eliciting responses and reposts from the likes of Dexter King and Sarah Jessica Parker. Harriman’s photography also caught the eye of Edward Enniful, the Editor In Chief of British Vogue, and history-making happenings quickly followed; this September, the Nigerian-born Misan became the first Black man to shoot the cover of British Vogue in its 104-year history.

“Edward allowed me a great amount of freedom. It’s such an important issue—great leadership and trust. He empowered me to feel that my work is good enough. It’s one thing to have influence, it’s another to give others a sense of belonging.”

The cover, featuring the British model and activist Adwoa Aboah and the British soccer player Marcus Rashford (who, alongside playing for Manchester United, has campaigned for the British government to give free summertime school meals to families affected by COVID-19), is part of the globe-spanning project by the magazine simply dubbed HOPE. The entire September issue—traditionally an approbation of highest ranks of couture fashion—is instead dedicated to ”the extraordinary voices, old and young, who in this difficult year have devoted their energies to fighting for a fairer society” wrote Enniful in his editor’s letter. The fold-out cover, emblazoned with the headline Activism Now, features19 activists, all shot in Harriman’s signature black and white.

“I concentrated on not fainting and focused on breathing, to make my way through the Zoom call with all my faculties, that’s the honest answer,” he says of finding out about the high-profile gig. On that fateful call were Enninful and his senior Vogue team. “The Vogue team came across my work of civil rights photography, which became incredibly viral over the past few months,” he explains in a phone call from London. “Of course, the EIC made some incredibly powerful statements (on social media) with some of my images, so that’s how they came across me. The genius of Edward is that he knew before me or anyone else that the way I shoot, the way I capture honesty and emotion, is exactly what was needed for this issue. I believe the results have spoken for themselves.”

“I wanted to collect a time capsule of the biggest civil rights movement in modern history, something I never thought I’d live to see the day of. My images show a lot of hope and solidarity. People from all walks of life, all races, that are out there, fighting against one of the biggest stains of modern man.”

While the photoshoot was styled by Donna Wallace, with hair by Earl Simms and makeup by Celia Burton (a predominately Black team), Harriman applied his creative vision and his lens to create the end result. “Edward allowed me a great amount of freedom,” he says. “It’s such an important issue—great leadership and trust. He empowered me to feel that my work is good enough. It’s one thing to have influence, it’s another to give others a sense of belonging.” After Enninful became the first Black man to lead British Vogue in 2017, the magazine’s representation of BIPOC significantly increased, both on the pages and behind the scenes. The photoshoot, Harriman says, was the ideal example of how representation and empowerment work: “I call it a symphony of activism—he orchestrated it perfectly,” he says. “He’s a man of deep empathy and incredible purpose. And if you merge these two things with having influence, those three things can make you literally a world changer in the industry.”

The photographer Misan Harriman, photographed by Camilla Holmstroem.

Despite the fact that his photography career began only three years ago, after his wife bought him a camera and urged him to start shooting, Harriman’s no stranger to the power of the image. In 2016, he founded What We Seee, a digital media platform that curates and creates content on entertainment, inspirational lives, the arts, and world affairs, both on the web and social media. Photography is an extension of his passion for storytelling and documenting humanity. “When the death of George Floyd happened, I thought, anything I can do is use my own weapon, which is my camera, to add to this story,” Harriman says. “I wanted to collect a time capsule of the biggest civil rights movement in modern history, something I never thought I’d live to see the day of. My images show a lot of hope and solidarity. People from all walks of life, all races, that are out there, fighting against one of the biggest stains of modern man.” Understandably, his photography idols are Gordon Parks, the self-taught American photo documentarian known for his civil rights imagery, and Mo (Mohamed) Amin, the Kenyan photographer whose devastating depiction of famine in Ethiopia led to the initiation of LiveAid. Both men, beyond documenting history as it unfolded, sparked impactful conversations and pushed for change. Does he believe documenting the protests in 2020 is a form of activism? “It’s whatever you want it to be—that’s the beautiful thing about photography,” says Harriman. “I’ve been shooting protests for the last few years; I want my lens to be an observation of the human condition.”

“A lot of Black people, in pretty much any modern society, are walking with what I call open wounds. We’ve had so many years of not having a voice, it’s become normalized to internalize our frustrations. And what happened is that all of those frustrations came out.”

Yet by design, Harriman’s work, culminating in the buzzy Vogue cover but by no means stopping there, brings issues of racism and inequality to the surface. Speaking louder than slogans, it’s impossible to look away from. “A lot of Black people, in pretty much any modern society, are walking with what I call open wounds,” he says. “We’ve had so many years of not having a voice, it’s become normalized to internalize our frustrations. And what happened is that all of those frustrations came out. Many of my friends and I are dealing with big traumas, small traumas; everyone’s experience with any country with institutionalized racism is different. My experience has been one of deep reflection, and education, as well.” In the UK, if anything, matters are “well behind the U.S,” he says. “We don’t have a mature enough entertainment industry to have Black-owned production companies.” He speaks of racism across the board, from “trying to hail a taxi and having thirteen taxies drive past me,” to lack of representations on boards and in key leadership positions. But, just like the latest British Vogue issue, his mission is all about hope, as well as “education, solidarity. If my images can help those who suffer from racism, or are learning about racism, then I’m happy.” And as for people of color, who are yet to meet their mentors and benefactors, yet to receive their cameras, who’ll be flipping through the pages of Vogue in search of inspiration and perhaps doing battle with self-doubt, Harriman says: “I want to use this attention to let those who maybe never have thought they had a chance to get into photography, fashion or media, know that the door is open, and my hand is outstretched to pull them in.”