The art of Protest

At a new exhibition at the de Young Museum in San Francisco, local artists respond to a year like no other, tackling issues of police brutality, protest, pandemic, isolation, inequality and so much more.

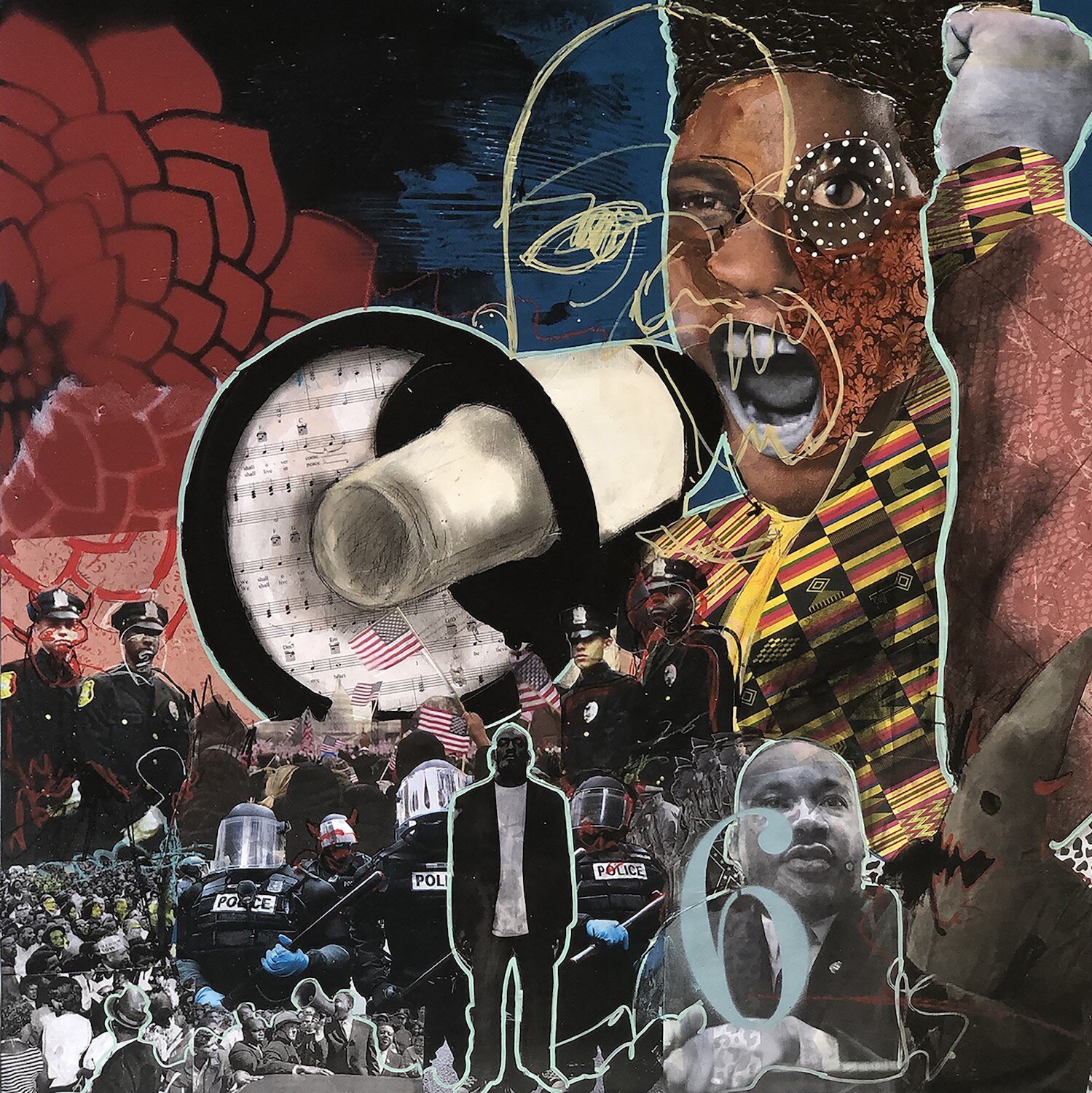

Orin Carpenter “Sick and Tired” 2020, image courtesy of the artist

If you attended any protests this summer, you know the feeling of suddenly being shoulder to shoulder with masses of emotionally charged people—an especially jarring sensation after months of pandemic-induced isolation. Walking through The de Young Open, the new exhibition at San Francisco’s beloved institution, the sensation is not dissimilar. Nearly 1,000 artworks of every medium are displayed gallery style, with mere inches between their edges. The visual stimulation and expressed emotion are a lot to take in. But what about this year hasn’t been a lot to take in?

Out of 11,514 submissions in response to the de Young’s open call, 877 artworks by 762 artists were selected. And as you walk into the opening gallery the Black Lives Matter theme is unmistakable. It’s a progressive follow up to last year’s The Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power 1963-1983. The de Young Open is a masterfully curated and executed tour-de-force exhibition that showcases local talent, including a trio of artists from the Three Point Nine Art Collective, a group founded in 2009 to address the issue of Black people disappearing from San Francisco. Cheryl Derricotte, Mark Harris, and Ron Moultrie Saunders all have pieces in the first gallery, and each of them play on themes they have been exploring for over a decade—and that a large segment of the world is just waking up to.

The opening gallery at The de Young Open,

“At Three Point Nine Art Collective we’re always presenting work from the perspective of a Black artist and talking about our place in San Francisco,” says Saunders, one of the collective’s co founders. “When viewers come to see our work, we always have a discussion about the presence of Black people and some of the elitism that happens in SF, access, and equity. We’ve been having these conversations as a collective with the public for ten years. So the fact that all these things have come to the surface now, yeah, it’s about time. Because only those people who are willing to have those open conversations would step forward, and now everyone is forced to.”

“When viewers come to see our work, we always have a discussion about the presence of Black people and some of the elitism that happens in SF, access, and equity. We’ve been having these conversations as a collective with the public for ten years. So the fact that all these things have come to the surface now, yeah, it’s about time.” -Ron Moultrie Saunders

Photography by John Arbuckle

The Three Point Nine Art Collective derived its name from an article in a local Bayview Black newspaper that projected the Black population in San Francisco would be 3.9% in the 2010 census. The figure turned out to be 6.1% but today the figure is between 3% and 5% pending the outcome of the 2020 census. But data aside, it’s Saunders' own personal experiences that have most pointedly shaped his views. When he first moved into the Bayview neighborhood 35 years ago it was a predominantly Black community. Now it’s flipped, with the Black population having dropped significantly. “So when that film (The Last Black Man in San Francisco) came out,” Saunders muses, “Yeah, I feel like the last Black man in San Francisco. There’s a lot of ambivalence about the changes that are happening. People feel like they are being pushed out.”

Asked whether he considers himself an activist, Saunders demurs, “I am an artist who is involved in my community. I really started becoming more active in the community in 2008 when I co founded a gallery in the Bayview. The way I’m active is by creating my work, putting it out there, sharing it through Three Point Nine Art Collective shows, and doing things like getting into the de Young Museum where we can have conversations about racism.” He is also involved in the First Exposures Photography Program, which offers no-cost photography instruction and mentoring to youth. “There are very few Black photographers in San Francisco. And very few Black artists. There is a group of us who want to be visible and want kids to know that there are people out there doing these things and you can do them too.”

Ron Moultrie Saunders’ Perhaps because of the near darkness you can see me

Saunders’ work at the de Young Open, Perhaps because of the near darkness you can see me, references the collective’s origin concept of San Francisco’s vanishing Black population, layered with the ebbs and flow of other populations both disappearing and appearing in the city in the last ten years.

Saunders shares, “The title for the piece is a reinterpretation of a line from The Invisible Man. The character is walking down the street. It’s almost dark. And this white man bumps into him and after that encounter he makes this comment to himself that, well, maybe he only saw me because it was near darkness. It plays on the idea of Black people being visible only at night because there’s a sense of danger when Black people are around at night.” Regarding the art itself Saunders says, “You can’t tell if the head is blending in, if it’s emerging, if it’s disappearing.” He purposely doesn’t provide much information so viewers have to bring themselves to the work.

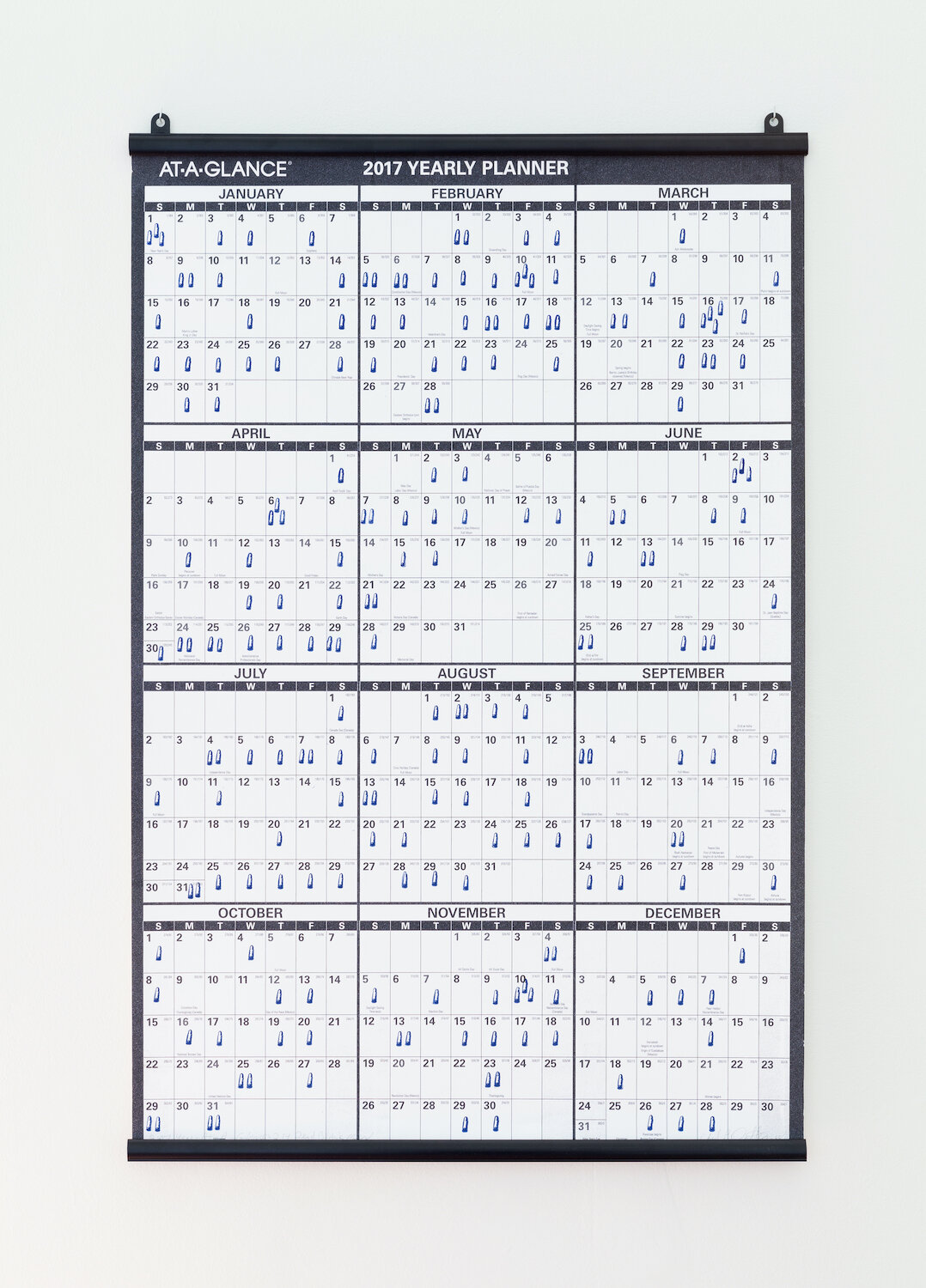

Cheryl Derricotte’s 2017 Year-at-a-Glance: 214 Dead Black Men

By contrast, Cheryl Derricotte’s 2017 Year-at-a-Glance: 214 Dead Black Men is meant to be more straightforward in the message it conveys. It’s a common year-at-a-glance calendar with hand-stamped bullets (often more than one per day) on each date a Black man was killed by police. “This artwork is a way for people to engage with the topic of police brutality in America through the lens of art. When you see all of those bullets you realize, wow, this is a really big problem. There are many days when there are multiple bullets on the same day, and each bullet is representing a Black man who was killed.” Derricotte has been developing other pieces in that series looking at other years of data, and the broad police killings of Americans of all races as well. She adds, “We have a really bad problem with police brutality and we also have a very big problem in this country with guns.”

When asked what inspires her work, Derricotte responds, “My own art and activism has always been shaped by antiracist work.” Her experience in antiracism advocacy extends from South African divestment to housing equality, but it started even earlier than memory. Discovering the intergenerational narrative, she learned that her mother used to take her in a stroller to marches to fight for mothers on welfare. She adds, “My art is a different form of activism. It’s contributing to the dialogue, and that’s why I view myself as a contemporary political artist. My work is a way for society to have difficult and necessary conversations around topics through the lens of art.”

Asked about what’s missing in the media, Derricotte responds, “Part of the great reckoning right now is that the media has an opportunity to show more positive images of Black people. We are bombarded with images of Black who are killed or somehow involved with the criminal justice system. This is a great opportunity to show that there are tons of Black people doing great things, living lives like other Americans. Those are narratives we need to see.”

“It’s been a great narrative to see women in leadership. There needed to be a movement and reckoning with Me Too, but we had to be present for stories of victimization and horror of women. I feel we need just as many stories of women doing great things and great work, so [victimization] is not the dominant narrative.”

“Part of the great reckoning right now is that the media has an opportunity to show more positive images of Black people. We are bombarded with images of Black who are killed or somehow involved with the criminal justice system. This is a great opportunity to show that there are tons of Black people doing great things, living lives like other Americans. Those are narratives we need to see.”

-Cheryl Derricotte

Photograph by Nye' Lyn Tho

“Last but not least, I feel like American society needs to do a better job of being a global citizen, to the extent that media can share positive international collaboration, not just among governments, but individually.” This year Derricotte participated in a micro residency with the French Consulate at Villa San Francisco, where French and American artists shared their art and conducted transdisciplinary dialogue.

For artist and collective member Mark Harris, inspiration comes from people and current events. “Because I love people, I believe in people and I believe in our capacity to change. I’m inspired to try and help facilitate that change. Artists are the antenna of society so I believe I’ve become a translator of what’s happening in the collective consciousness at this moment. And unfortunately inspiration is coming easy for me right now because of the challenges that we’re facing as a country on so many levels.”

Mark Harris’ Man to Man

Harris recalls the defining moment that made him identify as an activist, “Michael Brown’s murder in Ferguson, Missouri, six years ago. That’s definitely the watershed moment for me. That particular time and the events around the unrest in Ferguson was when I decided to pursue my art in a different way.“

Oprah Winfrey’s indelible acceptance speech for the Cecil B. DeMille Award at the 2018 Golden Globes inspired Harris’s de Young Open piece Man to Man. “She used her platform to speak to the moment. She spoke about violence against women in Hollywood. It was bold, engaging, and inspiring. At the end of her speech she said, ‘Their time is up,’ and received a standing ovation.” When he heard it, Harris knew that phrase belonged with an advertisement from an old Life magazine he saved nearly three years earlier. It was originally anti-communist propaganda used during the Red Scare in the McCarthy era. Harris rewrote the imagined conversation between father and son, bringing white male privilege into focus. An American flag and stamp motif directly references the USA Forever stamp, but in this piece the flag is miniaturized and dragging on the ground, symbolizing a fallen empire.

As the country starts to recognize the many issues that Black people have long been familiar with, Harris notes, “If anything, it’s given me more clarity and resolve on what it is that I’m doing and the need to continue. Activism is about starting where you are with what you have.”

He adds, “[The pandemic] provided a front row seat for everybody to see the George Floyd tragedy.” However, “seeing the problem is not enough. That’s just the start. There has to be action. So that’s where I feel the role of the artist comes in. We’re trying to get people to see and acknowledge these tragedies. Give them some inspiration, give them some fuel, spur them into action. I’ve been heartened and encouraged by the fact that so many more people see it or are starting to see it and wake up to it. You gotta start somewhere. This is a start to what is a long journey.”

“Michael Brown’s murder in Ferguson, Missouri, six years ago. That’s definitely the watershed moment for me. That particular time and the events around the unrest in Ferguson was when I decided to pursue my art in a different way.“ - Mark Harris

The de Young Open is now open to the public until January 3, 2021 and tickets are available for purchase on the de Young Museum site. The artists will be able to offer their pieces for sale and retain all proceeds.